- Home

- Psychologist & Psychiatrist C&P Examiners

- Disability Exams Research

Disability Exams Research

June 22, 2024 – Disability exams research published in peer-reviewed academic journals, books, and related publications, with an emphasis on disability among United States military veterans.

On this page:

- CAPS-5-R

» Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5, Revised

» Citation

» Abstract

» CAPS-5-R Article Excerpts (Jackson et al. 2024) - C&P Exams and VA Disability Determination: Study Demonstrates Equitable Consideration of Women Veterans ... Based on Exams Conducted at a Fully Staffed, University-Affiliated C&P Exam Clinic with an Active Quality Improvement Program

- Concerns About the Morel Emotional Numbing Test (MENT)

» Worthen & Moering (2011)

» Recent Research Supports Our Concern About Morel Emotional Numbing Test Interpretation

» Citation (Williamson et al. 2024)

» Abstract (Williamson et al. 2024)

» MENT Score Interpretation - Trauma Exposure and Transdiagnostic Distress

- MST-related PTSD Service Connection: Characteristics of Claimants and Award Denial Across Gender, Race, and Compared to Combat Trauma

- Functional Disability in U.S. Military Veterans

- C&P Exams for MST-related PSTD: Examiner Perspectives

- Disability Exams Research - Archives (pre-2022 research articles)

PTSDexams.net is an educational site with no advertising and no affiliate links. Dr. Worthen conducts Independent Psychological Exams (IPE) with veterans, but that information is on his professional practice website.

CAPS-5-R

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5, Revised

Citation

Jackson, B. N., Weathers, F. W., Jeffirs, S. M., Preston, T. J., & Brydon, C. M. (23 August 2024). The revised Clinician‐Administered PTSD scale for DSM‐5 (CAPS‐5‐R): Initial psychometric evaluation in a trauma‐exposed community sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.23093

Abstract

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is a widely used, well-validated structured interview for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It was recently revised to improve various aspects of administration and scoring. We conducted a psychometric evaluation of the revised version, known as the CAPS-5-R.

Participants were 73 community residents with mixed trauma exposure (e.g., sexual assault, physical assault, transportation accident, the unnatural death of a loved one).

CAPS-5-R PTSD diagnosis demonstrated good test–retest reliability, кs = .73–.79; excellent interrater reliability, кs = .86–.93; and good-to-excellent alternate forms reliability with the CAPS-5, кs=.79–.93.

In addition, the CAPS-5-R total PTSD severity score demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = .86; interrater reliability, ICC = .98; and alternate forms reliability with the CAPS-5, r = .95.

Further, the CAPS-5-R demonstrated good convergent validity with other measures of PTSD and good discriminant validity with measures of other constructs (e.g., depression, anxiety, alcohol problems, somatic concerns, mania).

Given its strong psychometric performance in this study, as well as its improvements in administration and scoring, the CAPS-5-R appears to be a valuable update of the current CAPS-5.

CAPS-5-R Article Excerpts (Jackson et al. 2024)

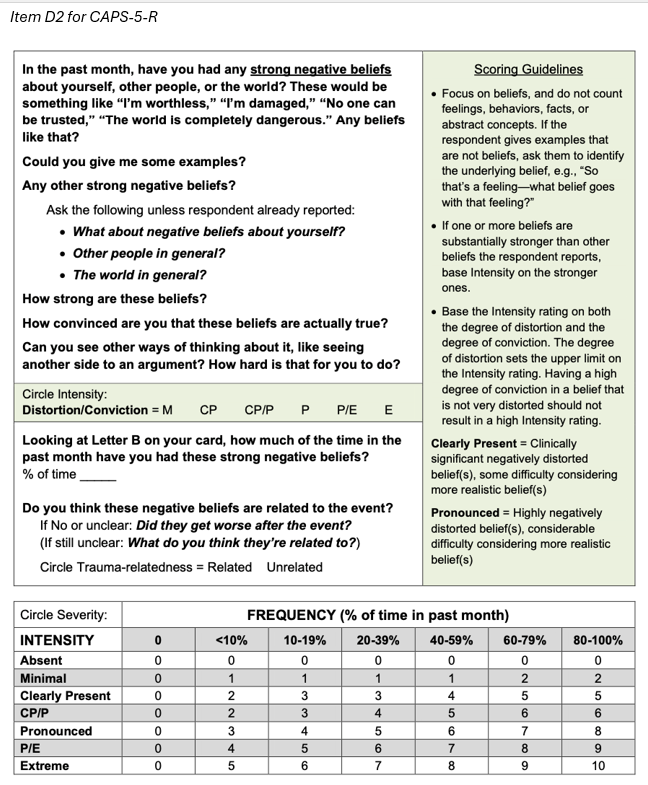

First, some existing prompts were modified, and new prompts were added to clarify inquiries and elicit more detailed information. ... Prompts were carefully reviewed and tested in role plays and actual interviews with trauma survivors to ensure they were conceptually accurate, easily understood, and effective at eliciting adequate responses.

Second, the scoring guidelines for each item were substantially expanded [and] supplemented with much more detailed information, including conceptual clarifications, e.g.,

for Item D2, “Focus on beliefs, and do not count feelings, behaviors, facts, or abstract concepts,” and specific rating instructions, e.g.,

for Item D2, “Base the intensity rating on both the degree of distortion and the degree of conviction.”

Third, the rating scale for item severity was expanded from 0–4 on the CAPS-5, to 0–10 on the CAPS-5-R, resulting in an increase in the possible range for total symptom severity from 0–80 to 0–200.

This created a more granular rating scale to detect smaller differences in symptom severity and address a possible restriction of range in CAPS-5 scores [since] a preponderance of [CAPS-5] items [are] scored as moderate or severe, with relatively few scored as mild or extreme.

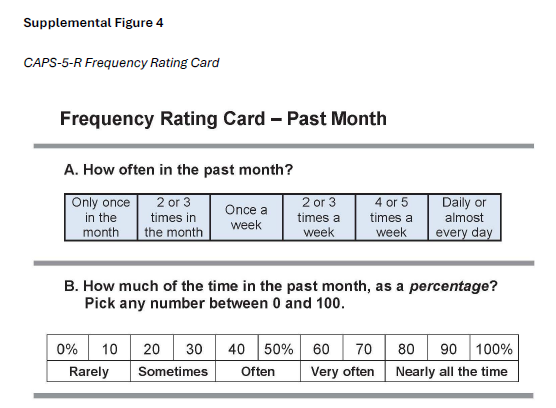

Frequency options were expanded to once a month, two or three times a month, once a week, two or three times a week, four or five times a week, and six or seven times a week. Items for which frequency is rated as a percentage of time were revised similarly.

Fourth, a frequency response card was developed to reduce respondent burden and promote more accurate estimates of symptom frequency.

The card contains four rating scales corresponding to each of the four types of frequency responses required on the CAPS-5-R. Each scale provides a range of fixed options intended to help respondents more quickly identify an appropriate frequency rating for a given symptom.

C&P Exams and VA Disability Determination: Study Demonstrates Equitable Consideration of Women Veterans

... Based on Exams Conducted at a Fully Staffed, University-Affiliated C&P Exam Clinic with an Active Quality Improvement Program

CITATION

Gianoli, M. O., Meisler, A. W., & Gordon, R. (2024). Examining bias in the award of Veterans Affairs (VA) disability benefits for posttraumatic stress disorder in women veterans: Analysis of evaluation reports and VA decisions. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.23034

ABSTRACT

Studies have raised concerns about possible inequities in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)'s awards of disability for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to women. However, the diagnoses and opinions made by disability examiners have not been studied.

A sample of 270 initial PTSD examination reports and corresponding VA decisions were studied. Compared to men, women veterans were as likely to be diagnosed with a service-related mental disorder and be granted service-connection.

Women veterans were considered to have more psychiatric symptoms, and more psychiatric impairment, but the percentage of disability awarded by the VA did not differ.

Secondary analyses implicate the role of military sexual trauma and premilitary trauma in explaining sex differences in symptoms and impairment.

The findings indicate that neither opinions by examiners nor corresponding decisions by the VA regarding service connection reflect a negative bias toward women veterans.

Results indicate that unbiased examinations lead to equitable VA claims decisions for women veterans.

Future studies of the VA PTSD disability program nationally, including examination procedures and VA policies and implementation, will promote equity for women veterans in the PTSD claims process. [Statistical data omitted, emphasis added, paragraph breaks added to facilitate online reading.]

QUOTE (limitations)

... it remains unknown if similar results would be obtained at other VA facilities or regions or from the VA’s Medical Disability Examination Office (MDEO) program (i.e., non-VA or “contract” exams).

All exams for the current study were conducted at VA Connecticut where there is:

(a) a large team of psychologists with experience conducting C&P exams and evaluating and treating veterans with PTSD and other mental disorders,

(b) team leadership with an active quality improvement program in place, and

(c) a climate strongly committed to equity and inclusion.

Concerns About the Morel Emotional Numbing Test (MENT)

Worthen & Moering (2011)

In our Practical Guide article, Dr. Robert Moering and I recommended that C&P examiners “consider using the MENT in Initial PTSD exams, along with the other measures mentioned earlier, e.g., the MMPI-2.”[1]

At the same time, we cautioned that “it is not yet known how many combat veterans with genuine PTSD intentionally perform poorly on the test because they naively believe that they are ‘supposed to’ fail the test because they have PTSD.”

We based this concern on our clinical impression: “Our anecdotal experience is that some veterans produce a MENT score above the recommended cutoff when all other evidence indicates they have genuine PTSD.”

Recent Research Supports Our Concern About Morel Emotional Numbing Test Interpretation

Williamson et al. (2024) found that psychological factors other than dissimulation, such as diagnosis threat, exert an influence on some veterans, resulting in higher MENT error scores for veterans with genuine PTSD.[2],[3]

The authors describe the MENT administration instructions as “deceptive” and question the ethics of these instructions. I do not believe the MENT violates APA ethical principles because, in part, other scholars argue that “such deception is necessary … and psychologists satisfy ethical responsibilities in the informed consent process through the explanation in general terms that validity measures will be used.”[3a]

But I agree that the MENT instructions are akin to a “leading question” for some veterans and likely lead to higher MENT scores for a nontrivial number of veterans with genuine PTSD.

The Williamson et al. (2024) study found that Veterans who received generic test instructions (no mention of PTSD) produced a median score of two errors, whereas the standard instructions, which indicate that the MENT is a PTSD test, resulted in a median score of three errors.

In addition, with the standard instructions 37% of the subjects “failed” the MENT, i.e., they produced 8 or 9 errors, compared to an 8% failure rate in the generic instructions condition.

Note that these research subjects received clinical neuropsychological evaluations, i.e., these were not forensic evaluations. Three veterans were service connected for PTSD, but the evaluations were not C&P exams; the veterans were referred for clinical reasons.

I do not believe this study invalidates the MENT as a legitimate PVT for use in forensic psychological evaluations, including C&P exams. Instead, it reinforces a foundational principle of forensic psychological assessment, i.e., that we should always consider the possibility that elevated scores represent something other than significant exaggeration or feigning.

In addition, I do not know how one could develop a PVT for PTSD without introducing the measure as a PTSD test. To do otherwise would defeat the purpose of identifying dissimulation for a specific disorder.

In my estimation, ethical use of the MENT requires:

- Including a statement in one's informed consent document truthfulness and accuracy will be assessed in a variety of ways, and that examinees should respond honestly to all questions during interviews and on questionnaires or psychological tests.

- Assiduously exploring alternative explanations for MENT scores above the standard cut score.

- Develop an interpretation rubric of your own, similar to the tables below, based on your understanding of the extant empirical literature and its application to MENT score interpretation.

Citation

Emily S Williamson et al., The Importance of the Morel Emotional Numbing Test Instructions: A Diagnosis Threat Induction Study, 39 Aʀᴄʜ. Cʟɪɴ. Nᴇᴜʀᴏᴘsʏᴄʜᴏʟ. 35 (2024).

Abstract

Objective

Marketed as a validity test that detects feigning of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the Morel Emotional Numbing Test for PTSD (MENT) instructs examinees that PTSD may negatively affect performance on the measure. This study explored the potential that MENT performance depends on inclusion of “PTSD” in its instructions and the nature of the MENT as a performance validity versus a symptom validity test (PVT/SVT).

Method

358 participants completed the MENT as a part of a clinical neuropsychological evaluation. Participants were either administered the MENT with the standard instructions (SIs) that referenced “PTSD” or revised instructions (RIs) that did not. Others were administered instructions that referenced “ADHD” rather than PTSD (AI). Comparisons were conducted on those who presented with concerns for potential traumatic-stress related symptoms (SI vs. RI-1) or attention deficit (AI vs. RI-2).

Results

Participants in either the SI or AI condition produced more MENT errors than those in their respective RI conditions. The relationship between MENT errors and other S/PVTs was significantly stronger in the SI: RI-1 comparison, such that errors correlated with self-reported trauma-related symptoms in the SI but not RI-1 condition. MENT failure also predicted PVT failure at nearly four times the rate of SVT failure.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that the MENT relies on overt reference to PTSD in its instructions, which is linked to the growing body of literature on “diagnosis threat” effects. The MENT may be considered a measure of suggestibility. Ethical considerations are discussed, as are the construct(s) measured by PVTs versus SVTs.

MENT Score Interpretation

Dr. Moering and I recommended a conservative MENT cut score of 18 (instead of 8 or 9).[3b]

Morel (2013) argued against this proposal based on a sophisticated mathematical analysis and classification accuracy statistics. He concluded that “there is theoretical justification and strong empirical evidence to continue the prevailing practice of using the standardized cutoff score on the MENT.”[4]

I found Morel’s arguments to be persuasive, but I nonetheless still worry that some veterans consciously or subconsciously underperform on the MENT, even though they actually have PTSD.

I modified my interpretation rubric based on Ken Morel's 2013 article, as reflected in the tables below, i.e., instead of a hard cut score of 18, I consider scores (for under age 60) of 8–12 as suggesting feigning, and 13–18 as likely feigning.

The standard cut scores, as indicated in the MENT manual are ≥ 8 for subjects under age 60 and ≥ 9 for older subjects.

My personal MENT interpretation tables[5] are below, but please keep in mind that other psychologists disagree with my conservative interpretation approach.

|

Younger Veterans (≤ 59) without neurocognitive disorder |

|

|

MENT Score |

Interpretation |

|

0–7 |

No evidence of feigning |

|

8–12 |

Suggests feigning |

|

13–18 |

Feigning likely |

|

19–36 |

Feigning |

|

37–60 |

Malingering[6] |

|

Older Veterans (≥ 60), or any Veteran with neurocognitive cognitive disorder[7] |

|

|

MENT Score |

Interpretation |

|

0–8 |

No evidence of feigning |

|

9–12 |

Possible feigning |

|

13–15 |

Suggests feigning |

|

15–19 |

Feigning likely |

|

20–36 |

Feigning |

|

37–60 |

Malingering |

Footnotes

[1] Mark D. Worthen & Robert G. Moering, A Practical Guide to Conducting VA Compensation and Pension Exams for PTSD and Other Mental Disorders, 4 Psʏᴄʜ. Iɴᴊ. & L. 187, 207–208 (2011), https://perma.cc/C9QK-MR23.

[2] Diagnosis threat is analogous to concepts such as confirmation bias, expectation effects, self-fulfilling prophecy, and nocebo effects. Most research on the phenomenon comes from neuropsychology. Briefly, prior to administering neuropsychological tests, if the psychologist mentions that the subject might have difficulty with cognitive tasks due to a history of head injury, those subjects exhibit more deficits on testing compared to similar individuals receiving the same evaluation for whom the psychologist omitted the statement about potential cognitive difficulties.

[3] Julie A. Suhr & John Gunstad, “Diagnosis Threat”: The Effect of Negative Expectations on Cognitive Performance in Head Injury, 24 J. Cʟɪɴ. Exᴘ. Nᴇᴜʀᴏᴘsʏᴄʜᴏʟ. 448 (2002) (article that first introduced the concept).

[3a] Shane S. Bush, Robert L. Heilbronner & Ronald M. Ruff, Psychological Assessment of Symptom and Performance Validity, Response Bias, and Malingering: Official Position of the Association for Scientific Advancement in Psychological Injury and Law, 7 Psʏᴄʜ. Iɴᴊ. & L. 197, 201 (2014).

[3b] Worthen & Moering (2011), supra note 1, at 208.

[4] Kenneth R. Morel, Cutoff Scores for the Morel Emotional Numbing Test for PTSD: Considerations for Use in VA Mental Health Examinations, 6 Psʏᴄʜ. Iɴᴊ. & L. 138, 141 (2013).

[5] These tables are based on my reading of the research literature, but they should be considered a rule of thumb, not a definitive guide.

[6] You have to concentrate intensely to intentionally choose the wrong option on this easy-to-answer PVT; there is only a 4.6% chance that a score of 37 or higher would occur by chance, e.g., flipping a coin. And, as Morel points out in the MENT Manual, the choices with the MENT are not by chance, so the actual odds of such a high error score (37) are exceptionally small. (Morel provides a mathematical explanation that is over my head, but his odds ratio has a trillion in the denominator.)

[7] See Thomas Merten, Comparative Data for the Morel Emotional Numbing Test: High False-Positive Rate in Older Bona-Fide Neurological Patients, 16 Psʏᴄʜ. Iɴᴊ. & L. 49, 54 (2023) (reporting a false positive rate of 34% for neurological patients over age 70).

Welcome To The Best Online HTML Web Editor!

You can type your text directly in the editor or paste it from a Word Doc, PDF, Excel etc.

The visual editor on the right and the source editor on the left are linked together and the changes are reflected in the other one as you type!

| Name | City | Age |

| John | Chicago | 23 |

| Lucy | Wisconsin | 19 |

| Amanda | Madison | 22 |

This is a table you can experiment with.

Trauma Exposure and Transdiagnostic Distress

CITATION

Crowe, M. L., Hawn, S. E., Wolf, E. J., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2024). Trauma exposure and transdiagnostic distress: Examining shared and posttraumatic stress disorder–specific associations. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.23009

ABSTRACT

We examined transdiagnostic and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)–specific associations with multiple forms of trauma exposure within a nationwide U.S. sample ( N = 1,649, 50.0% female) of military veterans overselected for PTSD.

A higher‐order Distress factor was estimated using PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) symptoms as indicators.

A structural equation model spanning three assessment points over an average of 3.85 years was constructed to examine the unique roles of higher‐order Distress and PTSD‐specific variance in accounting for the associations between trauma exposure, measured using the Life Events Checklist (LEC) and Deployment Risk and Resiliency Inventory Combat subscale (DRRI‐C), and psychosocial impairment.

The results suggest the association between trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms was primarily mediated by higher‐order distress (70.7% of LEC effect, 63.2% of DRRI‐C effect), but PTSD severity retained a significant association with trauma exposure independent of distress, LEC: β = .10, 95% CI [.06, .13]; DRRI‐C: β = .11, 95% CI [.07, .14].

Both higher‐order distress, β = .31, and PTSD‐specific variance, β = .36, were necessary to account for the association between trauma exposure and future impairment. Findings suggest that trauma exposure may contribute to comorbidity across a range of internalizing symptoms as well as to PTSD‐specific presentations.

Why is this Research Important for C&P Examiners?

The authors of this article stated: "PTSD is a necessary but not sufficient construct in that it captures reactions distinct from higher-order distress but does not represent the full range of trauma-related psychopathology."

Based on this research (Crowe, Hawn, Wolf, Keane, & Marx, 2024), we could (accurately) say that trauma independently causes PTSD, and that trauma directly causes depression. This is direct causation between an event and a mental disorder.

Event ⇢ Mental Disorder

Thus, a C&P psychologist could legitimately opine:

"It is more likely than not that traumatic experiences the veteran endured caused her major depressive disorder."

However, I suggest that you do not write your opinion like that.

When it comes to causality, C&P psychologists should consider the legal landscape. Specifically: "What type of causality is legally important?"

Direct (independent) causation is obviously important when conducting an initial PTSD exam since the primary objective is to determine if service-related1 trauma directly caused post-traumatic stress disorder.

But when you conduct an initial PTSD exam with a veteran and discover that he or she has PTSD and another mental disorder, you should think about causation differently.

You should think about the causal relationship between two mental disorders, where one mental disorder causes (or aggravates) a second mental disorder.2

Mental Disorder A ⇢ Mental Disorder B

If a C&P examiner opines that the veteran's service-related trauma caused major depressive disorder, such an opinion would complicate claim adjudication.

This is true because VBA adjudicates original (initial) claims for other mental disorders under a different standard of proof3 than initial PTSD claims.4

In addition, like all psychological evaluations, psychologists should answer the referral question. For Initial PTSD C&P exams the implied referral question is:

"If the veteran has another mental disorder (in addition to PTSD), is that mental disorder proximately due to or the result of PTSD?"

I say implied because the actual questions asked on the Initial PTSD DBQ are:

3a. Does the Veteran Have More Than One Mental Disorder Diagnosed?

YES NO (If “yes,” Complete Item 3b)

3b. Is it Possible to Differentiate What Symptom(s) is/are Attributable to Each Diagnosis?

(If "Yes," list which symptoms are attributable to each diagnosis and discuss whether there is any clinical association between these diagnoses)

The question about "clinical association" essentially asks:

"Is the other mental disorder proximately due to or the result of the PTSD?"

See 38 C.F.R. § 3.310 for the phrase "proximately due to or the result of."5

Finally, if you determine, during an Initial PTSD C&P exam, that a veteran has PTSD and another mental disorder, in most cases you should provide an opinion like this:

"It is more likely than not that the veteran's Major Depressive Disorder is proximately due to or the result of her Posttraumatic Stress Disorder."

Footnotes

1. I use the term service-related instead of service-connected because at the C&P exam stage, examiners proffer an expert witness opinion about the relationship between military service and a veteran's mental disorder(s), but the adjudicator—the Veterans Benefits Administration—makes the legal determination of service connection.

2. Two mental disorders can also exhibit bidirectional causality. Bidirectional causality means that two variables or factors influence each other mutually. It is not just that one variable (A) causes a change in another variable (B), but also that variable B, in turn, changes variable A:

Mental Disorder A 🡘 Mental Disorder B.

3. Posttraumatic stress disorder, 38 C.F.R. § 3.304(f)(3).

4. Principles relating to service connection, 38 C.F.R. § 3.303 (Jan. 11, 2024), and, for combat-related disorders, § 3.304(d).

5. Disabilities that are proximately due to, or aggravated by, service-connected disease or injury, 38 C.F.R. § 3.310 (Jan. 11, 2024).

MST-related PTSD Service Connection: Characteristics of Claimants and Award Denial Across Gender, Race, and Compared to Combat Trauma

CITATION

Webermann, A. R., Gianoli, M. O., Rosen, M. I., Portnoy, G. A., Runels, T.,

& Black, A. C. (2024). Military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress

disorder service-connection: Characteristics of claimants and award denial

across gender, race, and compared to combat trauma. PLOS ONE, 19(1), e0280708. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280708

ABSTRACT

The current study characterizes a cohort of veteran claims filed with the

Veterans Benefits Administration for posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to

experiencing military sexual trauma, compares posttraumatic stress disorder

service-connection award denial for military sexual trauma-related claims

versus combat-related claims, and examines military sexual trauma-related

award denial across gender and race.

We conducted analyses on a retrospective national cohort of veteran claims submitted and rated between October 2017-May 2022, including 102,409 combat-related claims and 31,803 military sexual trauma-related claims.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, logistic regressions assessed denial of service-connection across stressor type and demographics, and odds ratios were calculated as effect sizes.

Military sexual trauma-related claims were submitted primarily by White women Army veterans, and had higher odds of being denied than combat claims (27.6% vs 18.2%).

When controlling for age, race, and gender, men veterans had a 1.78 times higher odds of having military sexual trauma-related claims denied compared to women veterans (36.6% vs. 25.4%), and Black veterans had a 1.39 times higher odds of having military sexual trauma-related claims denied compared to White veterans (32.4% vs. 25.3%).

Three-fourths of military sexual trauma-related claims were

awarded in this cohort. However, there were disparities in awarding of claims

for men and Black veterans, which suggest the possibility of systemic barriers

for veterans from underserved backgrounds and/or veterans who may underreport

military sexual trauma.

Functional Disability in U.S. Military Veterans

CITATION

Meisler, A. W., Gianoli, M. O., Na, P. J., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2023). Functional

disability in US military veterans: the importance of integrated whole health

initiatives. Primary Care Companion For CNS Disorders, 25(4), 22m03461. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.22m03461

ABSTRACT

Objective: To examine the prevalence and sociodemographic, medical, and

psychiatric correlates of disability in activities of daily living (ADLs) and

instrumental ADLs (IADLs) in the US veteran population.

Methods: Data were analyzed from 4,069 US veterans who participated in the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (NHRVS). Multivariable and relative importance analyses (RIAs) were conducted to identify independent and strongest correlates of ADL and IADL disability.

Results: A total of 5.2% (95% CI, 4.4%–6.2%) and 14.2% (95% CI, 12.8%–15.7%) of veterans reported ADL and IADL disability, respectively. Older age, male sex, Black race, lower income, and deployment-related injuries were associated with ADL and IADL disabilities, as were certain medical and cognitive conditions. Results of RIAs revealed that sleep disorders, diabetes, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), older age, and cognitive disorders were most strongly associated with ADL disability, while chronic pain, PTSD, lower income, and sleep and cognitive disorders were most strongly associated with IADL disability.

Conclusions: Results of this study

provide an up-to-date estimate of the prevalence and sociodemographic,

military, and health correlates of functional disability in US veterans.

Improved identification and integrated clinical management of these risk

factors may help mitigate disability risk and promote the maintenance of

functional capacity in this population.

The image above and its caption are from a preprint of this article:

Petrich, L., Jin, J., Dehghan, M., & Jagersand, M. (2022, May). A quantitative analysis of activities of daily living: Insights into improving functional independence with assistive robotics. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 6999-7006). IEEE.

License: CC BY-SA 4.0, which requires, among other conditions, that you give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license.

These concepts (ADLs & IADLs) are increasingly important in disability exams research.

C&P Exams for MST-related PSTD: Examiner Perspectives

CITATION

Webermann, A. R., Nester, M. S., Gianoli, M. O., Black, A. C., Rosen, M. I.,

Mattocks, K. M., & Portnoy, G. A. (2023). Compensation and Pension Exams

for Military Sexual Trauma-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Examiner

Perspectives, Clinical Impacts on Veterans, and Strategies. Women's Health Issues, 33(4), 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2023.02.002

ABSTRACT

Background

It is estimated that in one in three women veterans

experience military sexual trauma (MST), which is strongly associated with

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A 2018 report indicated the Veterans

Benefits Administration (VBA) processed approximately 12,000 disability claims

annually for PTSD related to MST, most of which are filed by women. Part of the

VBA adjudication process involves reviewing information from a Compensation and

Pension (C&P) exam, a forensic diagnostic evaluation that helps determine

the relationship among military service, diagnoses, and current psychosocial

functioning. The quality and outcome of these exams may affect veteran

well-being and use of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) mental health care,

but no work has looked at examiner perspectives of MST C&P exams and their

potential clinical impacts on veteran claimants.

Methods

Thirteen clinicians (“examiners”) who conduct MST C&P

exams through VHA were interviewed. Data were analyzed using rapid qualitative

methods.

Results

Examiners described MST exams as more clinically and

diagnostically complex than non-MST PTSD exams. Examiners noted that assessing

“markers” of MST (indication that MST occurred) could make veterans feel

disbelieved; others raised concerns related to malingered PTSD symptoms.

Examiners identified unique challenges for veterans who underreport MST (e.g.,

men and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer [LGBTQ+] veterans), and

saw evaluations as a conduit to psychotherapy referrals and utilization of VHA

mental health care. Last, examiners used strategies to convey respect and

minimize retraumatization, including a standardized process and validating the

difficulty of the process.

Conclusions

Examiners’ responses offer insight into a process entered by

thousands of veterans annually with PTSD. Strengthening the MST C&P process

is a unique opportunity to enhance trust in the VBA claims process and increase

likelihood of using VHA mental health care, especially for women veterans.

License: CC BY-SA 4.0, which requires, among other conditions, that you give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license.

Archives

Previous posts about disability exams research can be found at: Disability Exams Research Archives.

Subscribe to receive new articles and other updates

What Do You Think?

I value your feedback!

If you would like to comment, ask questions, or offer suggestions about this page, please feel free to do so. Of course, keep it clean and courteous.

You can leave an anonymous comment if you wish—just type a pseudonym in the "Name" field.

If you want to receive an email when someone replies to your comment, click the Google Sign-in icon on the lower right of the comment box to use Google Sign-in. (Your email remains private.)

↓ Please comment below! ↓

- Home ›

- Psych Examiners ›

- Exam Research